Thunderstorms and severe thunderstorms

A thunderstorm is any cloud system that produces thunder and lightning. They are made up of one or more cumulonimbus clouds. These are tall, puffy, dark clouds that sometimes have an anvil-shaped top.

Thunderstorms are among nature's most dramatic sound and light shows – especially severe thunderstorms.

A typical thunderstorm lasts about 30 minutes to an hour. Severe thunderstorms can last many hours and travel long distances.

In Northern Australia, severe thunderstorms differ to those in southern and central Australia. Learn about tropical severe thunderstorms.

Video: Ask the Bureau: What is a thunderstorm?

Thunderstorms need three ingredients to form: The first ingredient is moisture. What we mean by that is moist, humid air that carries a lot of water vapour.

The second key ingredient for thunderstorms is a lifting mechanism. That is the force that makes the air move upwards, and quite often that can be a cold front moving in: where the colder, denser air lifts the air ahead of it. It could be air simply trying to cross a mountain range. It could be a sea breeze moving inland; or it could just be the heating of the day creating strong thermals and lifting the air higher and higher.

The third ingredient is atmospheric instability. This often comes in the form of cold air aloft and warm air lower down. That means that the warm air, as it rises into the cold air above it, can freely keep rising because it stays warmer than the environment, and therefore it can keep rising and the moisture in it condenses and forms the cloud.

A typical thunderstorm lives for about half an hour to an hour, and it goes through three stages in its evolution: The first stage is the towering cumulus stage, where the entire cloud consists of updraft – that is air rising.

The second stage it the mature stage. Now the thundercloud is at its largest size, and at its most organised. Now, in addition to the updraft, there's also a downdraft – that is air descending – and most of the heavy rain occurs in the downdraft. Then the cloud now also produces thunder and lightning. And another feature of the storm cloud now is what we call an anvil: That is the cloud spreading out sideways at its top, where the air can no longer rise any further, so the only place where it can go is sideways.

The third and final stage is the dissipating stage. That is where the energy supply to the storm is coming to an end, so the updraft and its downdraft are dying, and the cloud dissolves. Most thunderstorms in Australia form during the warm season, that is in the months of September through to March, but we can also experience cool-season thunderstorms, and they can form when the lifting mechanism is particularly strong. We can broadly forecast where and when thunderstorms form, but is it much harder to impossible to forecast where exactly and when exactly thunderstorms form. This is because very small differences in temperature and moisture make the difference between a large thunderstorm event and no thunderstorm event at all.

So if thunderstorms are forecast for your area, keep an eye on the Bureau's website for the latest warnings and also keep an eye on the radar to see whether storms are headed your way.

Definition of severe thunderstorm

A thunderstorm is classified as severe if it produces any:

- large hail – 2 cm in diameter or larger

- damaging wind gusts – 90 km/h or greater

- tornadoes

- heavy rainfall that may lead to flash flooding.

If we expect a thunderstorm to produce any of these, we issue a severe thunderstorm warning. Most thunderstorms don't reach the intensity needed to do this.

When and where severe thunderstorms hit

Severe thunderstorms can happen at any time of the year. Most happen between September and March, when there is usually more:

- solar energy

- moisture from warmer oceans.

In Australia's north, severe thunderstorms are less common during the dry season. In the south, they are less common during winter months. However, they are linked to cold fronts.

How thunderstorms form

Thunderstorms need 3 main ingredients to form.

Moisture

Moist, humid air that carries a lot of water vapour.

Unstable atmosphere

In an unstable atmosphere, temperature drops rapidly as height increases. This makes moist air more buoyant.

Lift

To make the moist air rise rapidly, it needs a lifting mechanism. For example, an approaching front or low pressure trough.

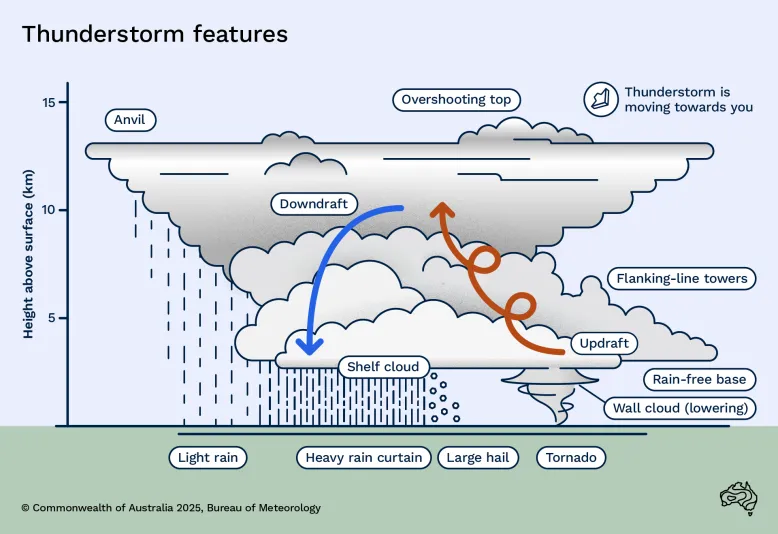

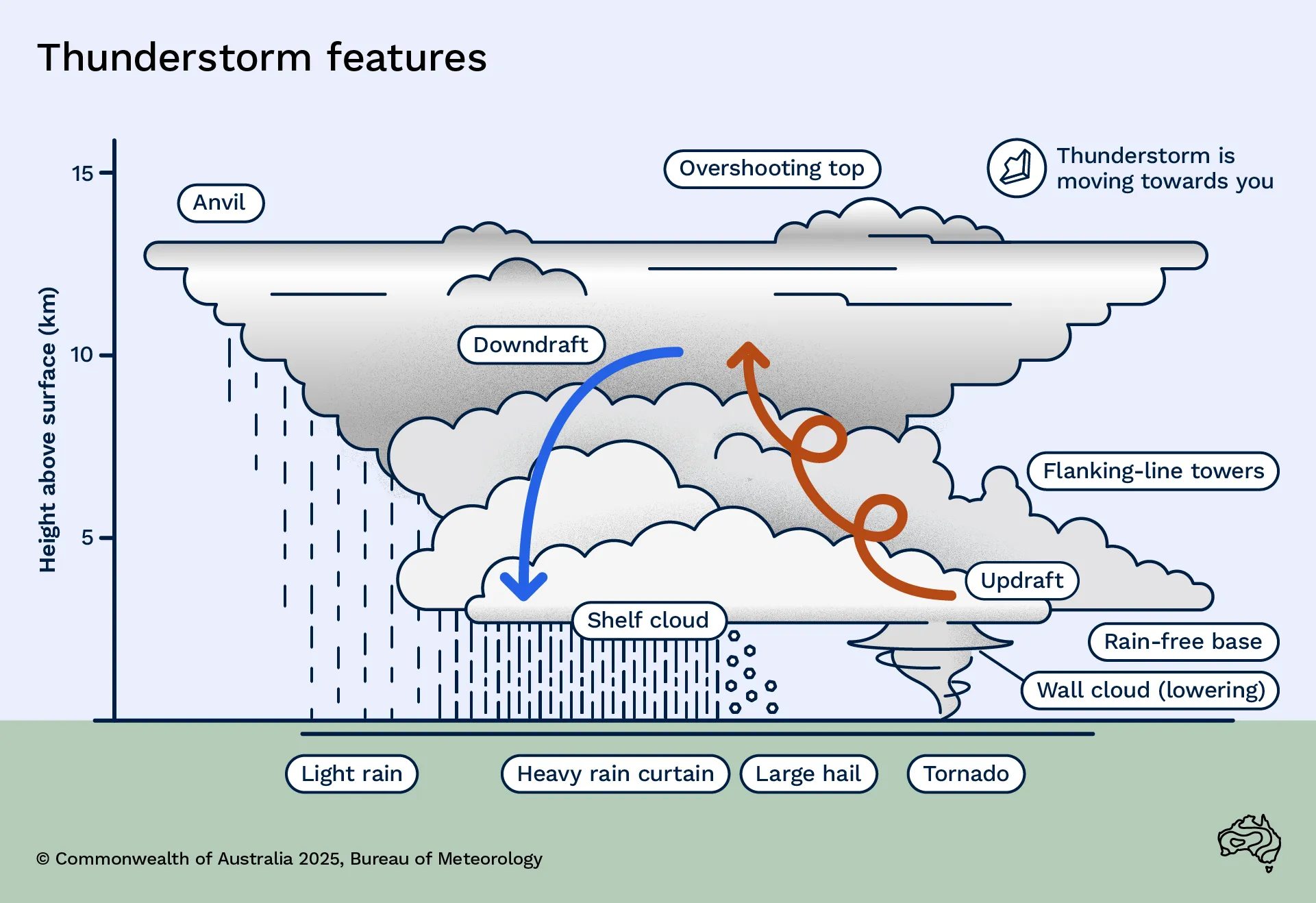

Parts of a thunderstorm

Updraft

Warm, moist air flowing into the storm, giving it energy.

Downdraft

A column of cool air that sinks toward the ground, most often along with rain.

Anvil

A flat, often wispy-looking cloud above and usually downwind of the updraft. The cloud is mainly made up out of ice crystals.

Outflow

Cool air flowing away from the storm, produced by evaporation of rain in the downdraft.

Flanking line towers

A line of cumulus clouds that connect to and extend out from the updraft of the parent cumulonimbus cloud. It usually looks like stair steps, with taller clouds closer to the parent cloud.

Wall cloud

An abrupt lowering of the cloud base. It descends from the relatively flat, rain-free base of a rotating supercell thunderstorm. Tornadoes often come from this part of the thunderstorm.

Shelf cloud

A low-level, wedge-shaped cloud marking the boundary between:

- warmer air ahead of the storm

- cool outflow air from the storm’s downdraft.

Types of thunderstorms

There are 3 general thunderstorm types: single-cell, multi-cell and supercell. Each has a distinct structure, circulation pattern, and set of characteristics.

Single-cell thunderstorm

A single-cell thunderstorm's life cycle is limited to the growth and collapse of a single updraft pulse.

The cloud forms, grows to maturity and produces a heavy downpour. It then decays as the cool outflow spreads out and descending air cuts off the original warm updraft.

These thunderstorms are most likely to happen on summer afternoons. They usually last no more than an hour and can produce strong wind gusts (microbursts). Developing single-cell storms can produce waterspouts or (over land) weak tornadoes.

It's rare to encounter a pure single-cell storm. Almost all of them have some multi-cell characteristics.

Multi-cell thunderstorm

Multi-cell thunderstorms are the most common. They consist of successive, separate updraft pulses. These pulses help maintain the system's overall strength, structure and appearance. They may be:

- very close together, so the thunderstorm is quite uniform over time, or

- widely spaced, so the thunderstorm goes through stronger and weaker phases.

Multi-cells can produce any of the thunderstorm phenomena. Tornadoes or giant hail are less common.

Supercell thunderstorm

This type of thunderstorm is very strong and can produce:

- damaging and destructive wind gusts

- heavy rainfall

- tornadoes

- large to giant hail.

They can last a long time, maintaining an almost steady state for many hours.

A supercell is distinguished by a deep and rotating updraft called a mesocyclone. This is a vortex within the thunderstorm.

Video: Ask the Bureau: What is a severe thunderstorm?

When we see or forecast these 'severe' thunderstorms, the Bureau issues warnings so people can keep themselves, their families and their property safe. All thunderstorms need three basic ingredients and they are: Warm, moist air at the surface; a lifting mechanism, forcing air upwards; and instability. Instability is where warm, moist air at the surface rises into the atmosphere above. In a typical thunderstorm the updraft transports the warm, moist air up through the storm. Now as the air cools and condenses, clouds and precipitation form; and once this precipitation becomes too heavy gravity takes over and pulls the rain and hail down to the surface with a cool gust of wind; and it's this cool air that acts to kind of interfere with the warm updraft, decaying the storm and leading to weakening.

For severe thunderstorms to form we need these three ingredients to be strong, but also a fourth ingredient, which is wind shear. Wind shear is the increasing speed with height, as well as a change in direction, as you move up through the atmosphere. The reason that wind shear is important is because it leads to tilting and rotation of the updraft into a kind of sloping corkscrew structure. This organisation means the cool downdraft is separated from the warm updraft, so you don't see any of that interference and weakening that we see in your garden-variety thunderstorms. This means that they can last many hours and travel long distances, potentially causing considerable damage.

So when the Bureau observes or forecasts conditions that support the formation of a severe thunderstorm – such as deep rotation, separation, as well as other important features – we issue a Severe Thunderstorm Warning.

The first thing we're concerned with is heavy rainfall, which may lead to flash flooding, and this is when the rate of rain is so high that water accumulates rapidly on the ground – faster than it can run off into drains and waterways. Rain like this has a potential to cause landslides, destroy homes and even carry away cars. The Bureau also warns for large or giant hail – greater than 2 cm in diameter – but we can get much larger than that.

When you get a highly organised severe thunderstorm, we can see cricket- to even softball sized hail – up to 10 cm in diameter. That can shred trees, damage cars, roofs and even houses. You definitely don't want to be outside in that. The third impact we warn for is damaging winds. A damaging wind gust is a gust in excess of 90 km/h, which can cause falling trees and other debris to damage houses, cars and crops. And also tornadoes: The Bureau will include tornadoes on a warning if we receive a verified tornado observation. While not as numerous or powerful as those seen overseas, Australia will see around 50 tornadoes every year and they can cause extremely strong winds in a localised area, which can cause major structural and property damage.

Lightning is another dangerous element of thunderstorms, but it occurs with all thunderstorms and not just severe ones. Sometimes regular storms can create severe weather, particularly when they form close together or line up; however, the most dangerous type of thunderstorm is a supercell thunderstorm.

Supercell thunderstorms are highly organised thunderstorms: They have a very deep rotating column of air, which tilts away from the downdraft. This means they can last a long time: Four to even eight times longer than your regular thunderstorms.

The peak season for severe thunderstorms in Australia is from around September through to March or April, although we can see severe thunderstorms in the winter months as well – these are mostly connected to strong cold fronts across southern parts of Australia.

So whenever severe thunderstorms affect your area, keep an eye on the satellite or radar to see if storms are headed your way and always get the latest forecasts and warnings via the Bureau's website or the BOM Weather app.

Thunderstorm phenomena

Thunderstorms can bring a range of phenomena. This includes heavy rain, thunder and lightning, hail, wind gusts and even tornadoes.

Thunder and lightning

Lightning is electrical discharge. It happens when there are large voltage differences between:

- the ground and part of the storm, or

- between parts of the storm.

The difference in voltage needs to be several million volts. That is, large enough to overcome the insulating effect of the air.

Lightning strikes can happen:

- within the cloud

- between clouds

- between clouds and the ground.

Thunder is the sound produced by the explosive expansion of air. The lightning heats the air to temperatures as high as 30,000° C.

To see the annual variation in thunderstorm and lightning activity across Australia, view the average annual thunder day and lightning flash density maps.

Hail

Hail is solid precipitation, in the form of balls or pieces of ice known as hailstones.

Hailstones can form in a thunderstorm with a strong updraft. Small particles of snow with a thin crust of ice (called graupel) are suspended in the updraft. They can sweep up small cloud droplets, which freeze onto the graupel surface. This means they can grow fast.

Hailstone diameter can range from 5 mm to more than 100 mm. Most are smaller than 25 mm. Hailstones larger than lawn bowls have been recorded in Australia. For example, a hailstone with a maximum diameter of 160 mm was recorded during a hailstorm in Yalboroo, Queensland on 19 October 2021.

Damage from hailstones may include:

- crop damage from small hailstones (less than 20 mm diameter)

- vehicle damage from larger hailstones (more than 20 mm diameter)

- widespread damage from giant hailstones (greater than 50 mm diameter).

Giant hailstones measuring 5 cm across

Wind gusts

In a mature thunderstorm, falling rain and hail drag the surrounding air downwards. Evaporation from the raindrops and melting ice cools the nearby air. This creates a cold dense bubble of air that speeds down towards the ground.

When it reaches the ground, this downdraft creates a dome of cool air. It can spread sideways very quickly, producing a cool, gusty wind that can cause damage. Strong winds in the lowest 2 km of the atmosphere can enhance the downdraft.

Learn more about wind, gusts and squalls in our Marine knowledge centre.

Tornadoes

Tornadoes do happen in Australia and have caused significant damage. They are the rarest and most violent thunderstorm phenomena. Learn more about Tornadoes.