Tide and sea level observations and forecasts

On this page we explain how the Bureau measures and predicts tides and sea level. For the latest observations and forecasts, view Coasts and oceans.

Sea level and tides

Sea levels

We measure sea levels to:

- monitor tides and coastal hazards

- understand long term changes in sea level and climate

- keep ships and other vessels safe – for example, so navigators know whether water is deep enough for their ship's keel.

Tides

Most Australians are familiar with ocean tides through the regular rise and fall of the sea – high tide and low tide at local beaches. But tides involve the whole ocean, not just local effects. They also involve currents called tidal streams.

Tides are driven by changing patterns of gravitational pull between the earth, moon and sun.

The deep ocean is set in motion by imbalances between the pull of the moon and sun, and their opposing forces. This creates huge patterns of ocean movement that show up at the coast as the ebb and flow of the tide. These movements are also affected by the:

- earth's rotation

- details of underwater landscapes, continental shelves and coastlines.

At most places, it takes about 6 hours to change from low tide to high tide – but in some places it can take about 12 hours.

Derby in Western Australia has one of the largest tidal ranges in Australia. Mudflats become visible twice a day as the tide recedes.

Measuring sea level and tides

We're working to accurately measure sea level and record meteorological data in Australian and Pacific waters. Devices used to measure sea level are usually called tide gauges.

We gather sea level data from many tide gauges, including:

- gauges owned by port operators

- our Australian Baseline Sea Level Monitoring Array – 14 standard stations and 2 supplementary stations at Lorne and Stony Point in Victoria, owned by port operators

- tsunami monitoring stations.

Partner organisations check the height of the gauges. The survey data is archived by Geoscience Australia to help track the vertical stability of tide gauges relative to the nearby land.

We're also working with Pacific Island countries to develop sea level records for the Pacific region. For details, view our Climate and Oceans Support Program in the Pacific (COSPPac) page.

Predicting tides

We predict tides at more than 700 locations around Australia, Antarctica and the South Pacific.

Tide tables give the height and time of tide changes for more than a year into the future. We also predict tidal streams at a few places. Our predictions are made using computer programs that take into account:

- the ocean's response to astronomical (gravitational) forces

- average seasonal changes.

Tide predictions are very reliable but don’t always match the actual water level. This is due to the irregular effects of changing weather and ocean circulation.

Weather influences on tide height and time

The main reason that actual water levels deviate from tide predictions is changing weather conditions.

Often the height of the water may be a little higher or lower than predicted, while the time of high and low tide doesn’t usually differ from predictions much at all.

Lower barometric pressure tends to raise the sea level and higher pressures push it down.

Winds over coastal waters can change tide heights quite a lot. Distant storms can also drive changes to sea level.

Very large short-term deviations of sea level away from predictions are called storm surges – see Storm tides and storm surge on this page.

Much slower seasonal fluctuations in sea level are predictable and particularly noticeable in some locations, such as the Gulf of Carpentaria. Unseasonal climate episodes, such as El Niño and La Niña, can cause sea levels to remain above or below predicted tide heights for longer periods.

Types of tides

King tide

King tide is not a scientific term. It's widely used to describe any remarkably high tide. Big tides are a natural and predictable part of the tidal cycle.

The time of year they happen varies by location and between years. They can have very noticeable effects where the ocean meets the land – at beaches, estuaries, harbours and other coastal locations.

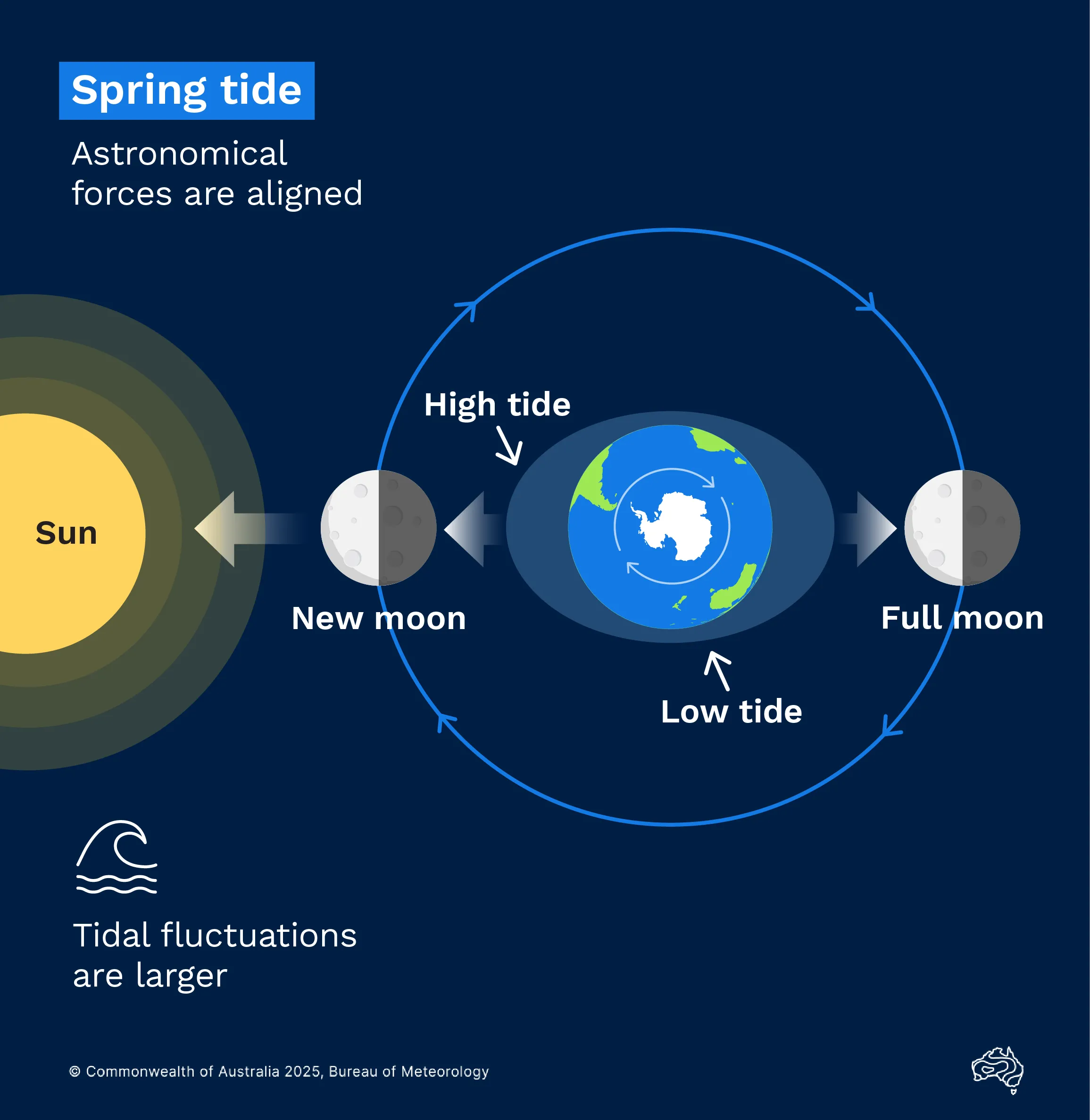

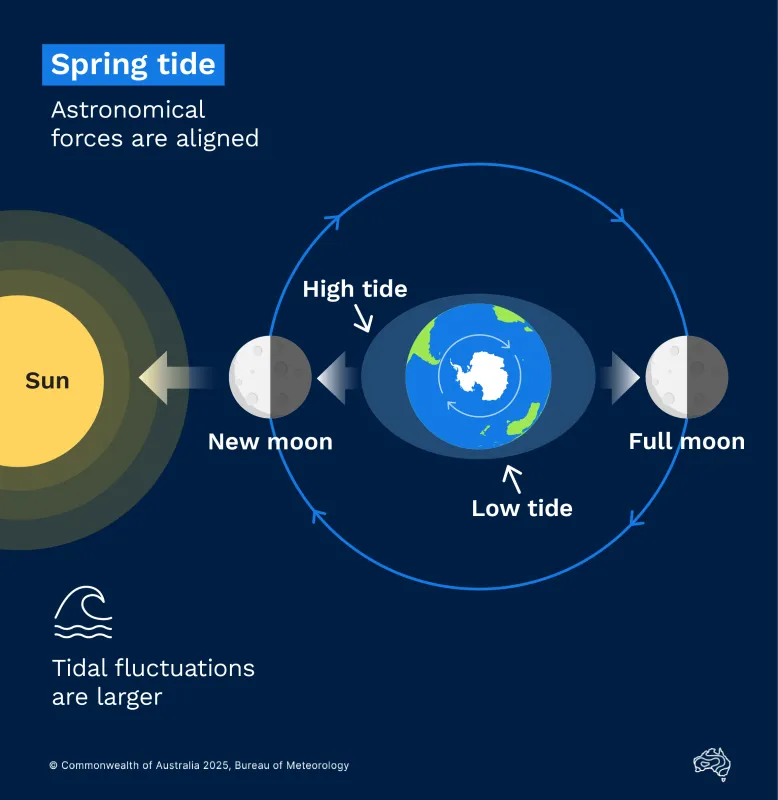

Spring tide

Spring tides typically happen every 15 days or so in areas that experience 2 high and 2 low tides in a day. The term 'spring tide' refers to 'springing forth', rather than to the season.

The forces that create tides are stronger when the moon, sun and Earth line up twice a month – at the new moon and full moon. In most places, more extreme ‘spring tides’ happen within a few days of these moon phases.

Spring high tides are a little higher than average. Spring low tides are a little lower than average.

The height of spring high tides varies across each year and across longer astronomical patterns. These long patterns mainly reflect the elliptical (oval) orbits of the earth and moon, and the relative tilts of these orbits.

The gravitational forces of the moon and sun work together to create spring tides. These are higher-than-usual high tides and lower-than-usual low tides.

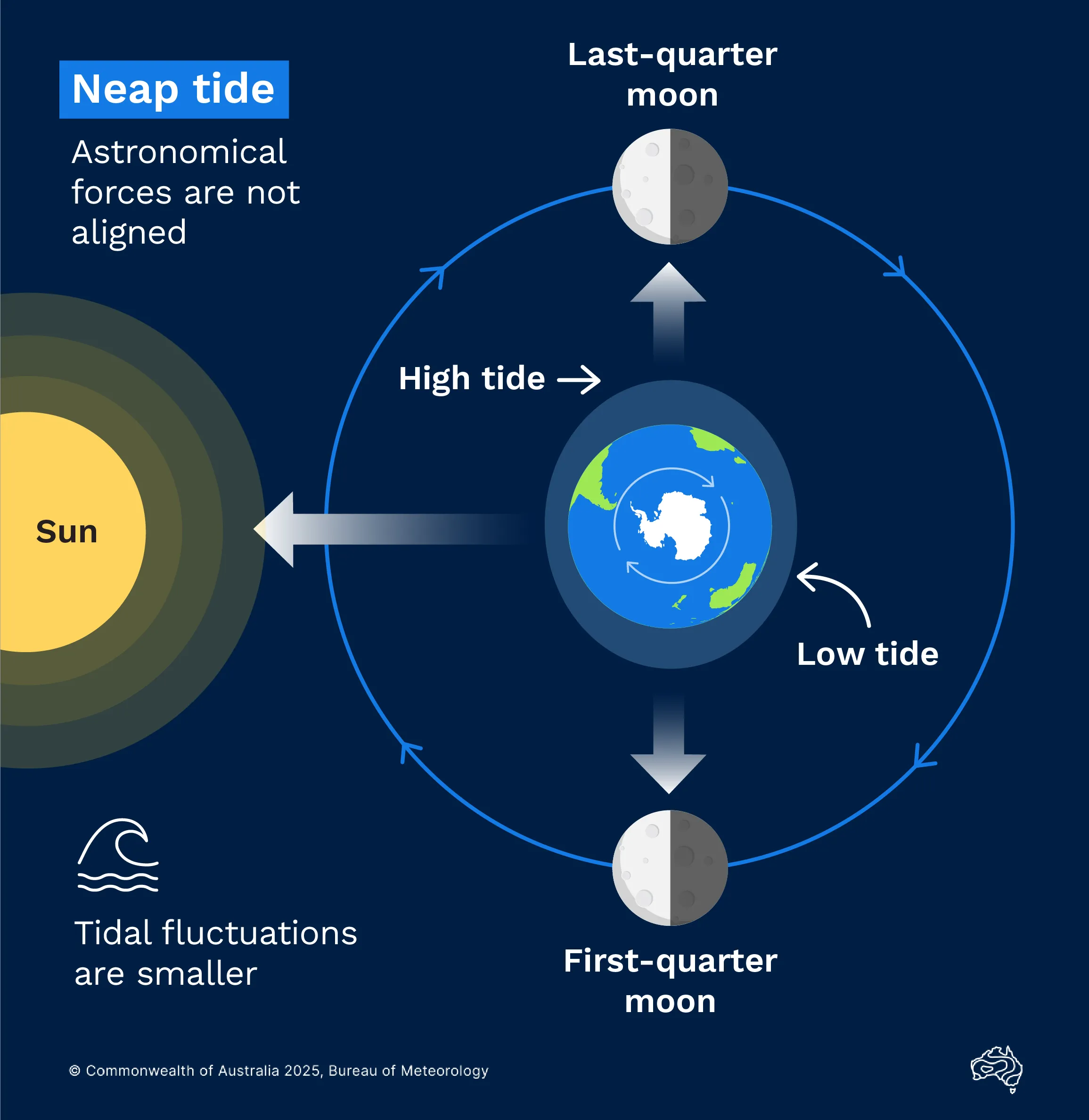

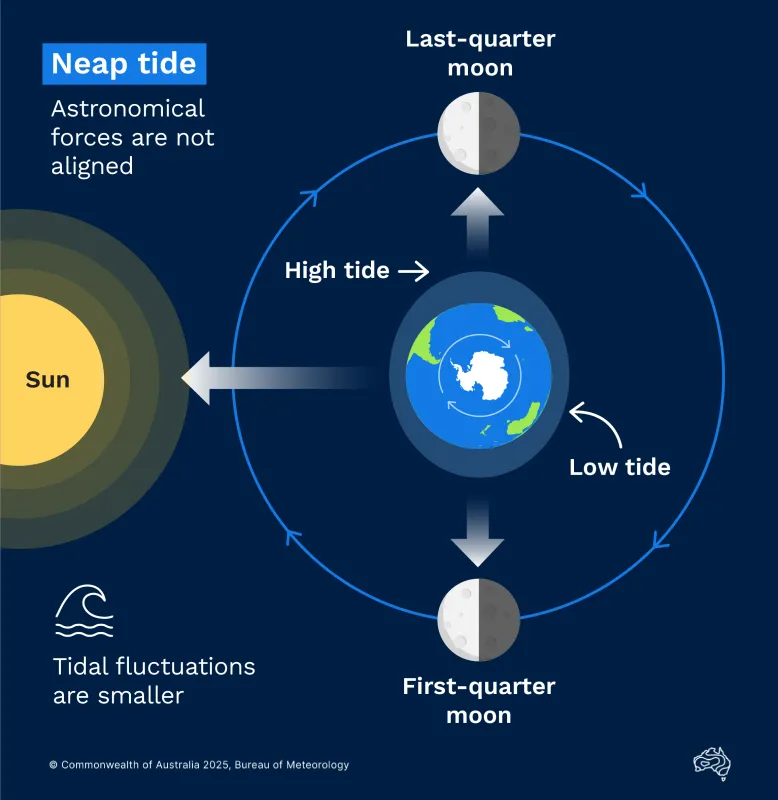

Neap tide

The more moderate tides around the time of quarter moons are called ‘neap tides' – that is, when the range of the tides is smaller than average.

During neap tides, the moon faces the earth at a right angle to the sun. Their gravitational forces work against each other.

Neap tides happen when the gravitational forces of the moon and sun pull at right angles to each other. This creates smaller differences between high and low tides than usual.

Dodge tide

In South Australia, a neap tide with minimal rise and fall over the course of a day or 2 has become known as a dodge tide.

This is what happens at Port Adelaide – the sea level recording gauge shows frequently little or nothing in the way of tide. In some cases, the level of the water remains almost constant for a whole day. In other cases, one small tide only occurs during the day.

On the days before and after a dodge tide, the tide is markedly irregular both in time and height. In the 1800s, it was difficult to predict. This possibly led to it being called 'The Dodger' in the local area.

This local phenomenon was first recorded in 1938 in the Official Yearbook of the Commonwealth of Australia, by Professor Sir Robert Chapman CMG:

"At spring tides the range, due to the semi-diurnal waves, is 2(M2 + S2), and at neaps, if the two are equal, or nearly equal, they practically neutralize one another and cause no rise nor fall at all."

Storm tides and storm surge

Storm surges are powerful ocean movements caused by wind action and low pressure on the ocean's surface. A storm surge raises sea level over and above the normal (astronomical) tide levels. The extra-high water levels resulting from the combination of normal tides, storm surge and waves are called storm tides.

Extreme storm tides can swamp low-lying areas and drive destructive flow over the land, sometimes for kilometres inland. Storm tides are especially dangerous when a tropical cyclone or large low-pressure system approaches land. But less extreme changes to tides are also caused by storms that are far away, even when the local weather is calm.

Forecasting storm tides

The paths of tropical cyclones are especially erratic, so forecasting the associated storm tide is difficult. The timing of the cyclone movement relative to normal high and low tides can be critical. Other elements contributing to the risk of storm surge include the:

- cyclone's speed and intensity

- angle at which the cyclone crosses the coast

- shape of the sea floor and local topography.

We provide technical predictions of extreme storm tide direct to emergency management authorities in areas impacted by tropical cyclones.

We also issue public warnings for storm tides not associated with tropical cyclones. The details of these warnings differ between states, but may refer to 'abnormally high tides' when included in a Coastal Hazards Warning. Learn more about coastal hazard warning services.

Difference between storm surge and tsunami

Storm surge differs from a tsunami.

A storm surge is generated by weather systems forcing water onshore over a stretch of coastline. It will normally build up over a few hours, as the cyclone or other weather system approaches.

A tsunami is generated by earthquakes, undersea landslides, volcanic eruptions, explosions or meteorites. These waves travel great distances, sometimes across entire oceans affecting vast lengths of coastal land.

Video: Understanding storm surge

Strong low pressure systems, especially tropical cyclones, create storm surges by physically pushing the water onshore. The stronger the winds, the higher the storm surge. Large storm surges can push water many kilometres inland. Which, combined with wind and pounding waves, can destroy buildings, wash away roads and pose threat to life.

Tidal range

Tidal range is the difference between the maximum and minimum water levels during a typical tidal cycle. This determines how much area is above water at low tide and under water at high tide – the 'intertidal zone'.

The tidal range influences the shape of beaches, as well as the marine life and marine activities in an area.

It's important to consider tidal range in your plans. The incoming tide can catch people unaware with deadly consequences. Tidal currents are typically stronger in areas of large tidal range or during periods of increased tidal range (spring tides).

Influences on tidal range

The differences in tidal range around Australia and the world are due to the:

- response of the ocean to astronomical tidal forces

- shape and depth of ocean basins, bays, and estuaries.

Large tidal ranges are often associated with wide continental shelves. Tidal ranges are not related to distance from the equator. At some locations the range is so small that the effects of waves and weather are more important.

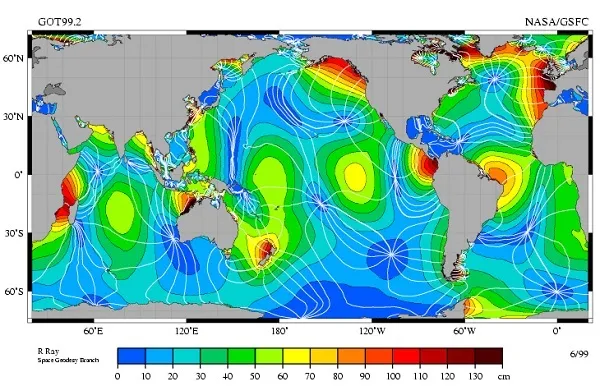

Scientists model ocean tides as a series of waves. These waves are so long that they move in regular patterns, shaped by the earth's rotation. They don't travel like waves at the beach, instead sweeping around basins like water swirling in a cup.

Each wave pattern appears to rotate around places called amphidromic points, or tidal nodes. The tidal range of the wave is very small near these nodes. South-west Australia has a small tidal range, as it is close to a node for a significant tidal wave called M2.

Understanding tide patterns as very large sweeping waves can also help explain why high tide times can often occur successively along a long stretch of coast.

Patterns for the M2 tidal wave show regular rotations about low-range places called amphidromic points, shown in dark blue. Credit: NASA.

Tidal ranges around Australia

The average tidal range varies dramatically around Australia's coast. For example, the tidal range is:

- less than 1 m in south-west Australia

- more than 8 m in north-west Australia, with changes of more than 11 m in one day during large spring tides.

Large tides are observed in Broome, in part due to the wide and relatively shallow North West Shelf. A similar effect occurs within the southern part of the Great Barrier Reef. It's an accident of underwater geography that both these locations are in the tropics – some tropical tides are tiny.

Of Australia's major ports, the largest tidal range can be found in Derby, Western Australia. At its most extreme, the tides there can change by more than 11.5 m in as little as 6 hours.

Around Australia, small tidal range can be found:

- across the southwest of Western Australia

- in the middle of the Gulf of Carpentaria

- in partially enclosed bays and estuaries such as Port Phillip, where Melbourne's tides typically change by less than 1 m.

Tidal streams

Tides are usually thought of as vertical movements – high or low. But this vertical movement comes about by water moving horizontally through ocean currents – tidal streams. Tidal streams are important for activities like boating and fishing.

Rising tides in bays, harbours and estuaries are associated with tidal streams flowing in from the ocean. These inward currents are called flood streams.

As the tides fall there will be a current flowing out towards the open ocean. This current is called an ebb stream.

Between the flood and ebb streams, there are periods of little or no flow – this is called slack water. Predicting the time of slack water can be important for planning underwater activities and shipping routes.

We provide tidal stream predictions for important shipping channels, such as Torres Strait, Queensland and The Rip at Port Phillip Heads, Victoria.