What is the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)?

Sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean can affect rainfall and temperature patterns over many parts of Australia. Warmer than average sea surface temperatures in the east of the Indian Ocean basin can provide more moisture for frontal systems and lows crossing the continent. This also increases the chance of clouds forming.

The difference between the sea surface temperatures of the tropical western (near Africa) and eastern (near Indonesia) Indian Ocean is known as the Indian Ocean Dipole, or IOD. This is one of Australia's climate factors.

The IOD has 3 phases:

- positive

- neutral

- negative.

Its influence can be seen across parts of eastern and southern Australia.

The IOD is only one factor in a complex system that influences Australia's climate. The best guide to the season ahead is our long-range forecast.

Timing of IOD events

IOD events usually:

- start around May or June

- peak between August and October

- rapidly decay when the monsoon arrives in the southern hemisphere around the end of spring or the start of summer.

IOD and El Niño or La Niña events can happen at the same time. When El Niño coincides with a positive IOD, this can reinforce dry effects. When La Niña coincides with a negative IOD, there's usually a greater chance of above-average winter-spring rainfall.

To see the IOD phases over the past decade, view the IOD Index time series in the climate monitoring graphs on our current website.

Video: Understanding the Indian Ocean Dipole

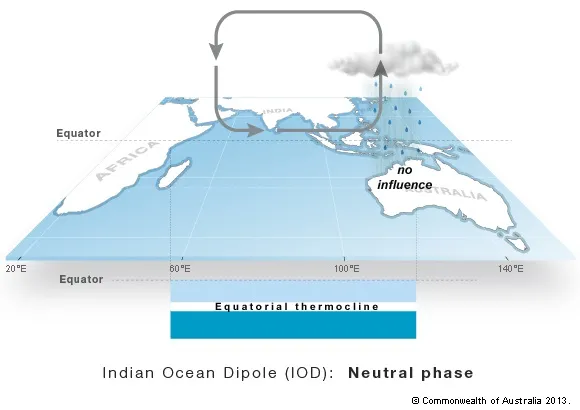

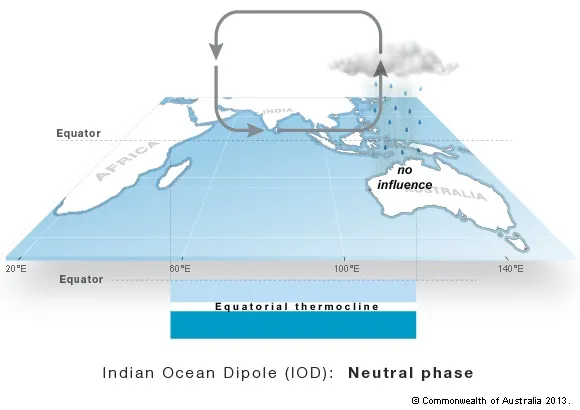

The IOD varies between three phases: positive, neutral and negative. On average each phase occurs about every 3–5 years. Positive or negative IOD phases usually begin in autumn or winter, and return to neutral around the end of spring when the northern Australian monsoon arrives. During a neutral phase, water from the Pacific flows between the islands of Indonesia, keeping seas to Australia's northwest warm. Air rises above this area and falls over the western half of the basin, blowing westerly winds along the equator. Temperatures are close to normal across the tropical Indian Ocean and the IOD has little influence on our climate.

During a negative phase westerly winds intensify, allowing warmer waters to concentrate near Australia. These stronger winds also mean it's harder for cool water to rise up from the deep near Indonesia. As these warmer waters move east, the clouds follow, favouring weather patterns that ultimately bring rain to southern Australia.

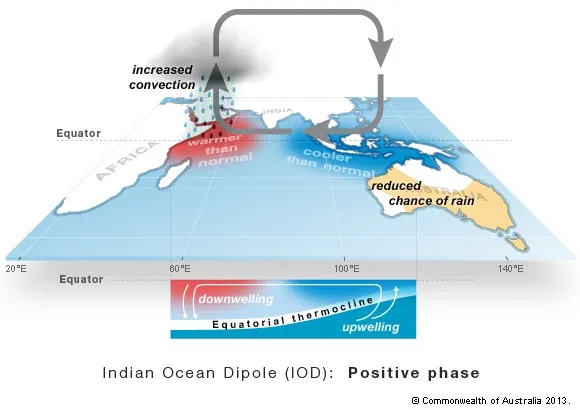

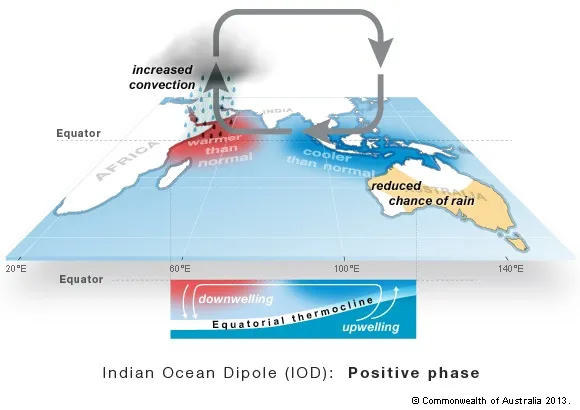

A positive IOD phase has the reverse temperature pattern in the Indian Ocean, and the opposite effect on Australia's climate. The westerly winds weaken and sometimes easterly winds form, allowing warm water to shift towards Africa. South of Indonesia, these changes in the winds allow cool water to rise up from the ocean depths. With cooler waters and descending air in the eastern Indian Ocean, less cloud forms. This changes the path of weather systems coming from Australia's west, often meaning less rain over central and southeast areas.

Often, but not always, a positive IOD coincides with the drying influence of the El Niño in the Pacific, both drawing rainfall away from Australia. For southeast Australia this can cause the failure of critical winter-spring rains and prime the land for severe summer fire seasons. For instance, 1982, the driest year on record for the region, was both a positive IOD and El Niño, and was followed by the devastating Ash Wednesday bushfires.

Likewise, a negative IOD can often occur during La Niña, both pushing more rain towards Australia. If both are strong, Australia can experience significant rainfall and widespread flooding. We saw this in two of the three wettest years on record for Australia, 1974 and 2010. Both years brought costly and deadly flooding to many areas. The Indian Ocean Dipole plays an important role in driving Australia's climate. No two Indian Ocean Dipole events and no two set of impacts are exactly the same. Understanding this key Australian climate driver can help you make smarter decisions.

Positive IOD phase

Westerly winds weaken along the equator, allowing warm water to shift towards Africa. Changes in the winds also allow cool water to rise up from the deep ocean in the east.

This creates a temperature difference across the tropical Indian Ocean – cooler than normal water near Indonesia and warmer than normal water near Africa.

Generally, this means less moisture than normal in the atmosphere to the north-west of Australia. It also changes the path of weather systems coming from Australia's west.

A positive IOD often results in less rain and higher than normal temperatures over parts of Australia during winter and spring.

Neutral IOD phase

Water from the western Pacific Ocean flows between the islands of Indonesia. This warms the seas to Australia's north-west.

Air rises above this area and falls over the western half of the Indian Ocean basin, blowing westerly winds along the equator.

Temperatures are close to normal across the tropical Indian Ocean. This means little change to Australia's climate.

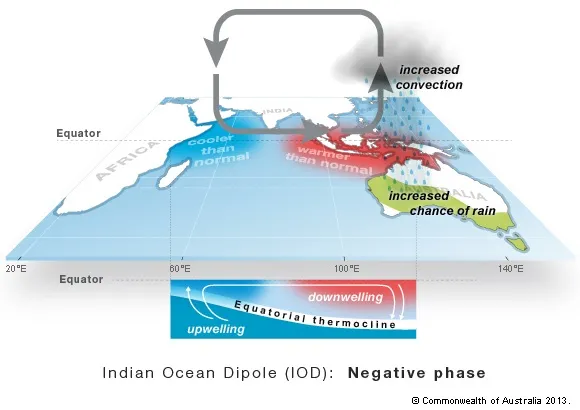

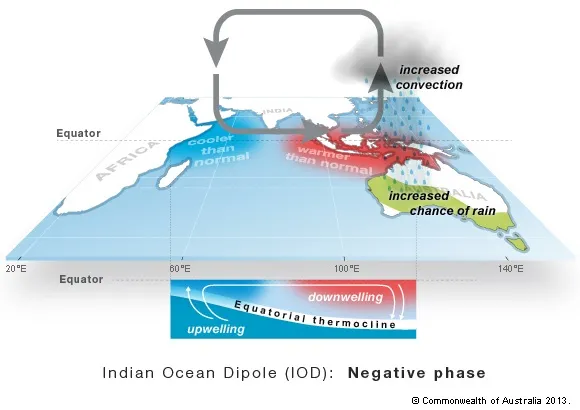

Negative IOD phase

Westerly winds intensify along the equator, allowing warmer waters to concentrate near Australia. This sets up a temperature difference across the tropical Indian Ocean, with warmer than normal water in the east and cooler than normal water in the west.

A negative IOD typically results in above-average winter–spring rainfall over parts of southern Australia. They make more moisture available to weather systems crossing the country.