El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

ENSO is a natural cycle in the Pacific Ocean that affects global weather, including across Australia. The cycle has 3 phases:

- El Niño

- Neutral

- La Niña.

The Neutral phase is the 'normal' state. El Niño (in Spanish, 'the boy') and La Niña ('the girl') are opposite parts of the cycle.

Each ENSO phase typically has a very different effect on the Australian climate. These effects can extend beyond the long-range forecast period.

ENSO is only one factor in a complex system that influences Australia's climate. The best guide to the season ahead is our long-range forecast. You'll find this on our current website – we're still building this new one.

How long do El Niño and La Niña last?

On average, El Niño occurs every 3 to 5 years. La Niña occurs every 3 to 7 years.

Both normally last about a year but can be shorter or much longer. Half of all La Niña events have lasted 2 or 3 years.

El Niño and La Niña typically:

- begin to develop in autumn/winter

- strengthen in winter/spring

- decay during summer and autumn of the following year.

The greatest impact on Australia's weather is in winter and spring – and for La Niña, into summer.

Video: Understanding ENSO

ENSO is a natural cycle in Pacific Ocean temperatures, winds and cloud. This influences climate right around the globe. In Australia, ENSO is often behind our climate extremes, from devastating floods to searing droughts. ENSO naturally swings between three key phases; La Niña, Neutral and El Niño. A typical ENSO phase starts in the first half of the year and lasts until the following autumn. Sometimes we can get the same phase for two or more years in a row. On average, it takes about four years to swing from El Niño to La Niña and back again.

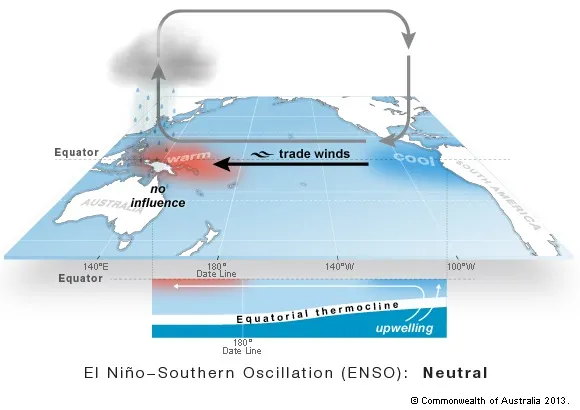

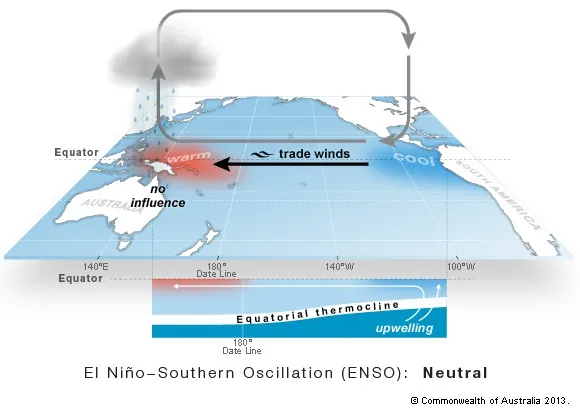

So what are these ENSO phases, and how do they impact Australia’s climate? Well during the neutral phase, steady trade winds blow across the tropical Pacific from the east to west. These winds pile up warm water in the western Pacific. In contrast, water temperatures to the east are lower as the trade winds cause cool water to be drawn up from the deep. The temperature difference across the tropical Pacific Ocean causes air to rise to Australia’s north, and descend near South America. This creates a huge connected cycle called the Walker Circulation. We consider neutral to be the 'normal' phase because we’re in this state more than half of the time. While a neutral phase may bring more ‘normal’ weather to Australia, droughts and floods are certainly still possible.

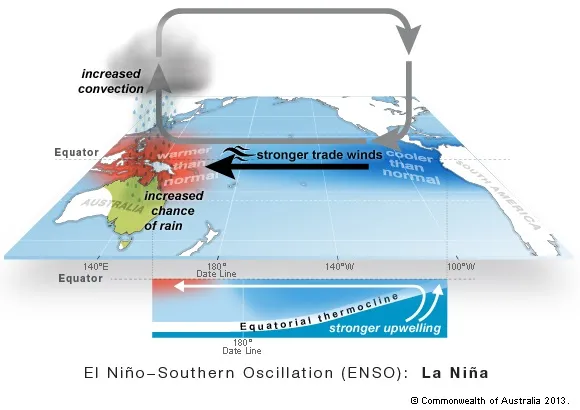

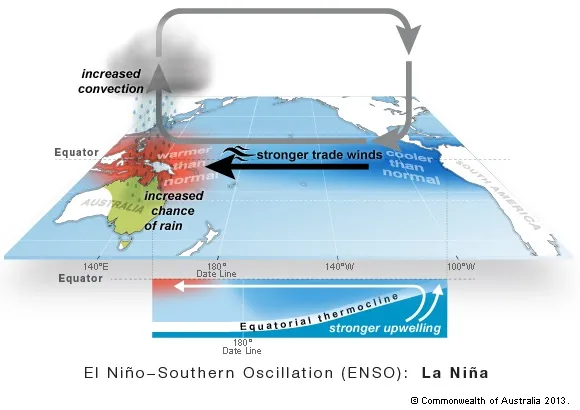

When we move into a La Niña, it’s a bit like the neutral phase has gone into overdrive. The trade winds blow harder, expanding the warm pool on the Australian side of the tropical Pacific, and cooling the oceans towards South America. This increases the east to west temperature difference, and makes the Walker circulation even stronger and the trade winds blow even harder again. This is called a feedback loop, and once it starts we’re locked into a La Niña until at least the following autumn. With the higher ocean temperatures, we get greater evaporation, more cloud and more rain in the western Pacific. For Australia, this means a higher risk of widespread flooding, lower daytime temperatures, and more tropical cyclones.

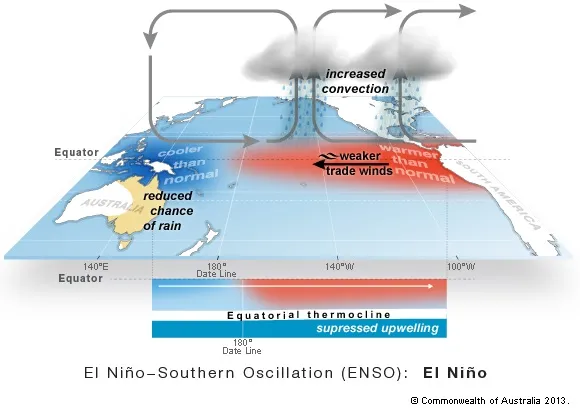

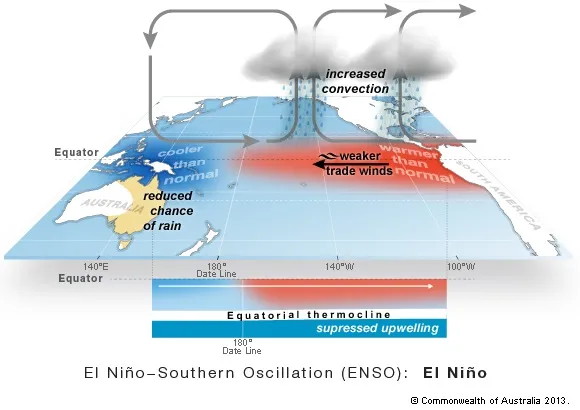

On the other end of the scale we have El Niño, which is almost the direct opposite of La Niña. During El Niño, the trade winds actually weaken, or reverse, allowing warmer waters to drift back towards the east. The change in the ocean temperature patterns mean the Walker circulation breaks down, resulting in even weaker trade winds, and even more warming in the east. Once this feedback starts, El Niño has set in. With the warm water shifting east, the evaporation, cloud and rain follows – shifting away from Australia. That means a greater risk of drought for northern and eastern Australia, higher temperatures and more heatwaves, clearer nights and a longer frost season, and fewer tropical cyclones.

While there are scientific definitions for El Niño and La Niña, in reality, no two events, and no two sets of impacts, are exactly the same. We also know some impacts will emerge as an ENSO event is developing, and some will persist even if an El Niño or La Niña never fully forms.

The Bureau updates the status of its ENSO tracker whenever an event may be on the horizon, so you can keep well ahead of the game. Understanding ENSO is a big part of understanding our climate, so stay up to date with our fortnightly ENSO Wrap Ups and of course, watch our monthly Climate Outlook videos.

About ocean currents and trade winds in the Pacific

In the eastern Pacific, the Humboldt current flows north. It brings cooler water from the Southern Ocean to the tropics. Along the equator, strong east to south-easterly trade winds blow. This causes ocean currents in the eastern Pacific to draw water from the deeper ocean towards the surface. This is called upwelling and it helps to keep the surface cool.

In the far western Pacific, there is no cool current. Weaker trade winds reduce upwelling. This means waters get warmer under the tropical sun. In normal conditions, the western tropical Pacific is 8–10° C warmer than the eastern tropical Pacific.

The ocean surface north and north-east of Australia is typically 28–30° C or warmer. (Near South America, the Pacific Ocean is close to 20° C.) This warmer ocean area is a source for convection – vertical movement of heat and moisture. It's associated with cloudiness and rainfall.

During El Niño years, the trade winds weaken and the central and eastern tropical Pacific warms up. This change in ocean temperature sees a shift in cloudiness and rainfall. It moves from the western to the central tropical Pacific Ocean.

El Niño phase

Trade winds weaken or reverse, and warmer surface water builds up in the central and/or eastern Pacific.

This change in temperatures shifts the clouds toward South America. This means:

- less cloudiness and rainfall north of Australia

- usually, below average winter–spring rainfall for eastern parts of the country

- later start to the northern wet season.

Neutral phase

Trade winds push warm surface water to the west and help draw up deeper, cooler water in the east. This is called upwelling.

The warmest waters in the equatorial Pacific build north of Australia, bringing cloudiness and rainfall.

La Niña phase

Trade winds strengthen and warm waters build up north of Australia. Waters in the central to eastern Pacific cool.

The change in temperatures across the Pacific affects where clouds form. There's more cloudiness and rainfall north of Australia. This typically leads to:

- above average winter–spring rainfall for eastern and central parts of the country

- an earlier start to the northern wet season

- lower daytime temperatures south of the tropics.

Video: La Niña in Australia

La Niña is a change in Pacific Ocean temperatures that affects global weather.

Typical impacts on our climate:

• Rainfall increases in eastern, central and northern Australia.

• Temperature decreases south of the tropics (daytime temperatures).

La Niña typically means:

• more tropical cyclones

• increased chance of widespread flooding

• longer duration heatwaves in southeast, but less intense

• earlier first rains across northern Australia

• increased chance of Indian Ocean heatwaves.

But every La Niña is different.

Rainfall during La Niña can vary considerably.

Bureau of Meteorology crest